Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Issue #142

by L. Swift and Jeff McQ

Anthony working at JITV session on The Van

Recording Connection grad Antony Montejo with band PPL MVR at Jam In The Van HQ in Los Angeles, CA

Read More

ON THE FINE LINE BETWEEN COMEDY AND DRAMA:

“The interesting part that I’ve learned over the years is that the rules between comedy and drama are essentially exactly the same. There’s no real difference. In fact, if you reduce all storytelling to, you know, defining the need and creating the obstacle which is the basis for all conflict, it applies equally to drama or comedy…If I described a film to you where two musicians witnessed a gangland massacre, a cold-blooded shooting of five, six people, and the musicians are discovered and they’re on the run for their lives, is that a comedy or a drama? Invariably, everyone says drama, but that is in fact the basis for the film the AFI voted the best American comedy of all time, Some Like It Hot by Billy Wilder. Because the comedy is not in the jumping off point—the comedy is in how the two protagonists run for their lives, and that’s why [they’re] joining an all-women traveling band and disguising themselves as women. And of course they’re incredibly testosterone-driven…and they’re surrounded by Marilyn Monroe and others and cannot reveal themselves. If they come out as men, they risk their lives. So therein lies comedy… It’s how the protagonist chooses to act to get around the obstacle that brings the comedy, but the jumping off point is always going to be equally as dire, equally as menacing and life-and-death as drama.”

ON THE SUBTLE WAYS COMEDY CAN COME INTO PLAY:

“Protagonists don’t have to be funny. The world around the protagonist can be funny. One of my favorite TV shows—and this is the perfect example—one of the best half hour sitcoms of all time to me is Arrested Development. Jason Bateman is the kind of sane center of that show, if you will, and the least funny character. Everyone around him is hilarious, but he’s kind of the anchor, the one person rooted in some kind of reality and, as such, plays the straight man and yet he is the show’s protagonist, he’s the one we relate to.”

ON THE CATHARTIC NATURE OF COMEDY:

“There’s a little cliché that comedy is tragedy plus time. Comedy is closer to tragedy than it is to drama…When you deal with a subject that is inherently tragic through a comedic approach, then by all means, it can be cathartic. I mean, a co-dependent, destructive male-female relationship can be Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? or it could be Annie Hall. So it’s both of those, and both are very cathartic films…I think the more serious the subject matter, the more potential there is for comedy…The great thing about comedy is it allows us to hold otherwise tragic or taboo subjects at arm’s length.”

THOUGHTS ON THE IMPORTANCE OF THEME IN SCREENWRITING:

I’m a big, big believer in theme. The most important thing you can have besides the situation and the approach and the tone, is theme because theme becomes your compass. It’s always pointing you true north. One of the best examples of theme I’ve ever seen is James Cameron’s Aliens, the sequel to Alien. The theme is the universality of motherhood. Ripley, who we know nothing about in the first Alien, turns out to be a single mom, turns out she promised her daughter she’d return for her 11th birthday, but because she’s been traveling in space at hyper-speed, she has aged differently than her daughter who’s now died of old age by the time she returns to earth. Ripley’s then sent back out into space where they think a colony has been infested with these aliens, and she finds a young girl named Newt, and she is determined to save Newt and redeem herself and not fail her like she feels she failed her daughter.

“Now in the meantime, and this is the brilliant part of the film, she goes up against the queen alien. In the first movie, the alien was basically an asexual parasite that thrives in a host’s body and then lives and grows. Here, we have The Queen; the biggest, baddest alien of them all, and that’s the ultimate antagonist. All the females in the movie are the strongest characters: the female marines and Ripley the protagonist. It is so much about the strength of the female of any species and the universality of motherhood, and that film is brilliant because of that.”

ON HOW THEME IS REVEALED IN A STORY:

“No one should set out to write a theme. No one sets out to write “war is hell” as a theme. No, you sit down to write a story, and as you’re working it out, you realize what you’re really saying is war is hell. And once you know that, that becomes your compass. Now there’s the danger of playing the theme versus playing the plot, and you don’t want to do that. You want to play the plot and let the theme come out of it. By way of example, going back to “war is hell,” if you have a scene with two soldiers in a foxhole in WWII and they’re talking about what hell they’re going through, that’s playing the theme. But if they’re in a foxhole and it’s winter, and if they don’t start a fire they’re going to freeze to death, but if they start that fire they’re going to alert the enemy snipers to their location and probably get shot, that’s hell. You don’t have to tell me: as the audience, I get it. So you don’t want the theme to dominate; you want the theme to play underneath and guide you, but you want to play the plot and let me, as the audience, get to the theme.”

ON THE FINE LINE BETWEEN COMEDY AND DRAMA:

“The interesting part that I’ve learned over the years is that the rules between comedy and drama are essentially exactly the same. There’s no real difference. In fact, if you reduce all storytelling to, you know, defining the need and creating the obstacle which is the basis for all conflict, it applies equally to drama or comedy…If I described a film to you where two musicians witnessed a gangland massacre, a cold-blooded shooting of five, six people, and the musicians are discovered and they’re on the run for their lives, is that a comedy or a drama? Invariably, everyone says drama, but that is in fact the basis for the film the AFI voted the best American comedy of all time, Some Like It Hot by Billy Wilder. Because the comedy is not in the jumping off point—the comedy is in how the two protagonists run for their lives, and that’s why [they’re] joining an all-women traveling band and disguising themselves as women. And of course they’re incredibly testosterone-driven…and they’re surrounded by Marilyn Monroe and others and cannot reveal themselves. If they come out as men, they risk their lives. So therein lies comedy… It’s how the protagonist chooses to act to get around the obstacle that brings the comedy, but the jumping off point is always going to be equally as dire, equally as menacing and life-and-death as drama.”

ON THE SUBTLE WAYS COMEDY CAN COME INTO PLAY:

“Protagonists don’t have to be funny. The world around the protagonist can be funny. One of my favorite TV shows—and this is the perfect example—one of the best half hour sitcoms of all time to me is Arrested Development. Jason Bateman is the kind of sane center of that show, if you will, and the least funny character. Everyone around him is hilarious, but he’s kind of the anchor, the one person rooted in some kind of reality and, as such, plays the straight man and yet he is the show’s protagonist, he’s the one we relate to.”

ON THE CATHARTIC NATURE OF COMEDY:

“There’s a little cliché that comedy is tragedy plus time. Comedy is closer to tragedy than it is to drama…When you deal with a subject that is inherently tragic through a comedic approach, then by all means, it can be cathartic. I mean, a co-dependent, destructive male-female relationship can be Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? or it could be Annie Hall. So it’s both of those, and both are very cathartic films…I think the more serious the subject matter, the more potential there is for comedy…The great thing about comedy is it allows us to hold otherwise tragic or taboo subjects at arm’s length.”

THOUGHTS ON THE IMPORTANCE OF THEME IN SCREENWRITING:

I’m a big, big believer in theme. The most important thing you can have besides the situation and the approach and the tone, is theme because theme becomes your compass. It’s always pointing you true north. One of the best examples of theme I’ve ever seen is James Cameron’s Aliens, the sequel to Alien. The theme is the universality of motherhood. Ripley, who we know nothing about in the first Alien, turns out to be a single mom, turns out she promised her daughter she’d return for her 11th birthday, but because she’s been traveling in space at hyper-speed, she has aged differently than her daughter who’s now died of old age by the time she returns to earth. Ripley’s then sent back out into space where they think a colony has been infested with these aliens, and she finds a young girl named Newt, and she is determined to save Newt and redeem herself and not fail her like she feels she failed her daughter.

“Now in the meantime, and this is the brilliant part of the film, she goes up against the queen alien. In the first movie, the alien was basically an asexual parasite that thrives in a host’s body and then lives and grows. Here, we have The Queen; the biggest, baddest alien of them all, and that’s the ultimate antagonist. All the females in the movie are the strongest characters: the female marines and Ripley the protagonist. It is so much about the strength of the female of any species and the universality of motherhood, and that film is brilliant because of that.”

ON HOW THEME IS REVEALED IN A STORY:

“No one should set out to write a theme. No one sets out to write “war is hell” as a theme. No, you sit down to write a story, and as you’re working it out, you realize what you’re really saying is war is hell. And once you know that, that becomes your compass. Now there’s the danger of playing the theme versus playing the plot, and you don’t want to do that. You want to play the plot and let the theme come out of it. By way of example, going back to “war is hell,” if you have a scene with two soldiers in a foxhole in WWII and they’re talking about what hell they’re going through, that’s playing the theme. But if they’re in a foxhole and it’s winter, and if they don’t start a fire they’re going to freeze to death, but if they start that fire they’re going to alert the enemy snipers to their location and probably get shot, that’s hell. You don’t have to tell me: as the audience, I get it. So you don’t want the theme to dominate; you want the theme to play underneath and guide you, but you want to play the plot and let me, as the audience, get to the theme.”

Read More

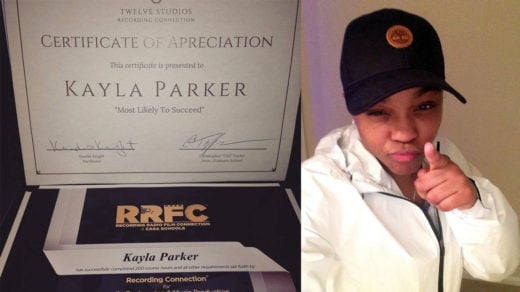

Recording Connection student Kayla Parker was recently got quite the surprise when she went into her mentor’s studio, Twelve Studios, to attend an awards reception and show her support for all the producers, engineers, and staff that make it happen. “I’m not a tall woman so I’m easily swallowed up by a room full of tall men,” she says. “Suddenly, I hear ‘Kayla Parker, is she still here?’ My mentor and advisor Christopher ‘CAT’ Taylor and Kandice Knight, alongside Twelve’s owner Dina Marto, presented me with the Most Likely to Succeed Award! I was in total awe.” Congrats Kayla! We believe in you!

Recording Connection student Kayla Parker was recently got quite the surprise when she went into her mentor’s studio, Twelve Studios, to attend an awards reception and show her support for all the producers, engineers, and staff that make it happen. “I’m not a tall woman so I’m easily swallowed up by a room full of tall men,” she says. “Suddenly, I hear ‘Kayla Parker, is she still here?’ My mentor and advisor Christopher ‘CAT’ Taylor and Kandice Knight, alongside Twelve’s owner Dina Marto, presented me with the Most Likely to Succeed Award! I was in total awe.” Congrats Kayla! We believe in you!

RRFC is education upgraded for the 21st century.

Get the latest career advice, insider production tips, and more!

Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Stay in the Loop: Subscribe for RRFC news & updates!

© 2025 Recording Radio Film Connection & CASA Schools. All Rights Reserved.