Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Issue #66

by L. Swift and Jeff McQ

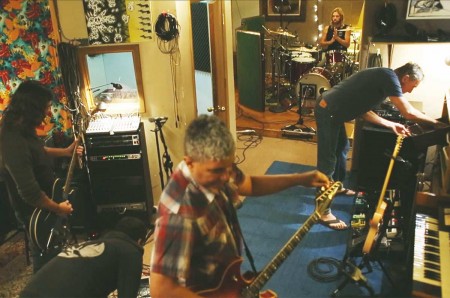

He says it like it’s a surprise to him. Recording Connection mentor Don Zientara seems to have trouble getting his mind around the fact that he’s been working in the music industry for upwards of four decades. In fact, talking with this unassuming producer/engineer and self-admitted gearhead, you’d never guess that he’s considered by many to be a giant in the annals of modern music history, having been a key figure in the emergence of the Washington, DC punk scene in the early 1970s.

You’d also never guess that he got there quite by accident.

As it turns out, the public was recently reminded about Don’s contributions to music when Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl featured him in an episode of the acclaimed HBO documentary series Sonic Highways, bringing the band in to Don’s Inner Ear Studio to track the song “The Feast and the Famine” for the album of the same name.

But as Don points out, that wasn’t the first time he and Grohl had worked together. Grohl grew up in the DC-area, and after the death of Kurt Cobain and the demise of Nirvana, Grohl returned to DC to record demos of some of his own songs with Don, for the purpose of recruiting the band that is now Foo Fighters. Don recalls working with Grohl, both recently and not-so-recently, particularly noting his openness to playing with lots of other musicians.

“He was always involved with musicians in terms of reaching out and playing with them, playing on their records, doing things like that,” says Don. “He’s just that kind of guy…There are just a lot of sensibilities that he has for both the studio and music, just hanging around and playing with people. And also, by giving of yourself unto other people’s projects, you find out things. And he did that. He just sort of absorbed it. He absorbed habits and he absorbed different little tricks of the trade…And it shows, too. You know, when he’s here, I learn things. And when the group was here, I learned things.”

He says it like it’s a surprise to him. Recording Connection mentor Don Zientara seems to have trouble getting his mind around the fact that he’s been working in the music industry for upwards of four decades. In fact, talking with this unassuming producer/engineer and self-admitted gearhead, you’d never guess that he’s considered by many to be a giant in the annals of modern music history, having been a key figure in the emergence of the Washington, DC punk scene in the early 1970s.

You’d also never guess that he got there quite by accident.

As it turns out, the public was recently reminded about Don’s contributions to music when Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl featured him in an episode of the acclaimed HBO documentary series Sonic Highways, bringing the band in to Don’s Inner Ear Studio to track the song “The Feast and the Famine” for the album of the same name.

But as Don points out, that wasn’t the first time he and Grohl had worked together. Grohl grew up in the DC-area, and after the death of Kurt Cobain and the demise of Nirvana, Grohl returned to DC to record demos of some of his own songs with Don, for the purpose of recruiting the band that is now Foo Fighters. Don recalls working with Grohl, both recently and not-so-recently, particularly noting his openness to playing with lots of other musicians.

“He was always involved with musicians in terms of reaching out and playing with them, playing on their records, doing things like that,” says Don. “He’s just that kind of guy…There are just a lot of sensibilities that he has for both the studio and music, just hanging around and playing with people. And also, by giving of yourself unto other people’s projects, you find out things. And he did that. He just sort of absorbed it. He absorbed habits and he absorbed different little tricks of the trade…And it shows, too. You know, when he’s here, I learn things. And when the group was here, I learned things.”

Interestingly enough, Don really had no aspirations of becoming a music industry icon—in fact, he relates that his interest in music was nominal at first, recalling that his Polish mother made him choose between learning accordion and guitar. (He chose guitar, he says, but put it down after a couple of years.) What he did love, though, was electronics, and tinkering with gear, which eventually rekindled an interest in guitar—particularly the electric guitar.

“Back in elementary school, I had friends that were involved in electronics and putting stuff together,” he says, “wiring circuitry, you know, getting huge electrical shocks and things like that. And they were basically just really, really smart…I always liked tape recorders, I’ve always enjoyed them, so I got some of these friends to help me and show me how to wire up a tape recorder to use it so I could plug my guitar into it and play through it…And from there, of course, I got into the guts of tape recorders and things like that and then the guts of amplifiers. And we would scour trash day and try to find old Magnavoxes and, you know, if they had any usable amplifiers or, hey a cabinet, maybe we could use this for a speaker cabinet or something like that if there were usable speakers in there.”

That interest in electronics eventually came back to serve him after being drafted for the army, when he found himself working at the National Gallery of Art. “There was a tour through one of the studios, [a] recording studio they were building for the guides, for the tours and little things like that. And they [had a] kind of problem with wiring, how to get a certain power supply in. And I said, ‘Well, here’s what you do, you have to just wire it up like this.’ And they said, ‘You know how to do this stuff?’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah.’ And they said, ‘Well, why don’t you become the engineer here?’ So I just sort of flipped from the artistic side. I became the audio engineer for the National Gallery. And then from that point on, I just stayed with audio and stayed with tape recording. And I just recorded everything I could possibly get my hands on.”

Interestingly enough, Don really had no aspirations of becoming a music industry icon—in fact, he relates that his interest in music was nominal at first, recalling that his Polish mother made him choose between learning accordion and guitar. (He chose guitar, he says, but put it down after a couple of years.) What he did love, though, was electronics, and tinkering with gear, which eventually rekindled an interest in guitar—particularly the electric guitar.

“Back in elementary school, I had friends that were involved in electronics and putting stuff together,” he says, “wiring circuitry, you know, getting huge electrical shocks and things like that. And they were basically just really, really smart…I always liked tape recorders, I’ve always enjoyed them, so I got some of these friends to help me and show me how to wire up a tape recorder to use it so I could plug my guitar into it and play through it…And from there, of course, I got into the guts of tape recorders and things like that and then the guts of amplifiers. And we would scour trash day and try to find old Magnavoxes and, you know, if they had any usable amplifiers or, hey a cabinet, maybe we could use this for a speaker cabinet or something like that if there were usable speakers in there.”

That interest in electronics eventually came back to serve him after being drafted for the army, when he found himself working at the National Gallery of Art. “There was a tour through one of the studios, [a] recording studio they were building for the guides, for the tours and little things like that. And they [had a] kind of problem with wiring, how to get a certain power supply in. And I said, ‘Well, here’s what you do, you have to just wire it up like this.’ And they said, ‘You know how to do this stuff?’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah.’ And they said, ‘Well, why don’t you become the engineer here?’ So I just sort of flipped from the artistic side. I became the audio engineer for the National Gallery. And then from that point on, I just stayed with audio and stayed with tape recording. And I just recorded everything I could possibly get my hands on.”

When Don says everything, he means everything. “One of the things that I learned from a lot of the people I was around was, grab every opportunity,” says Don. “And I just would [say], ‘I’ll record you. You wanna record? Man, I’ll record you. I don’t care if you are death metal, I don’t care if you are folk rock, I don’t care if you are hair metal, pop rock, metal metal, anything. I will record you. And I’ll learn…I did it with every music that I could possibly be in contact with.”

It was that very determination to take opportunities that landed Don at the forefront of DC’s punk movement, recording influential bands like Fugazi and Bad Brains, mainly because in many cases he was the only one who would. “No one would want to book a show with the punks,” he says. “I mean, they destroy things, they break things up, there’re fights and all kinds of other stuff. There’s blood all over the floor. And, as a matter of fact, when the Bad Brains were first here recording, [a friend] said, ‘Hey, why don’t you record these guys?’ And me, I don’t want to touch them. You know, they scare me. So I said, ‘Well hey, I’ll record them.’ You know, just anybody. I’ll record them. Like I said, I’ll record anything…These were sort of musical outcasts at the time, [but] today’s outcasts are tomorrow’s trendsetters.”

Don recalls that in the early days of the movement, he was recording bands using a mixing board he built himself, and the gear was subpar at best. But in his mind, it was all serendipitous. “At the time, everything lined up,” he says. “The fact that I wasn’t using the best equipment, but the punks’ music really didn’t count on having utmost fidelity. As a matter of fact, what they wanted was the experience in the moment, just capturing the moment. And that was something that I could give them…It’s surprising, it’s gratifying. I’m very proud of it. I feel… you know, I definitely embrace being part of it.”

When Don says everything, he means everything. “One of the things that I learned from a lot of the people I was around was, grab every opportunity,” says Don. “And I just would [say], ‘I’ll record you. You wanna record? Man, I’ll record you. I don’t care if you are death metal, I don’t care if you are folk rock, I don’t care if you are hair metal, pop rock, metal metal, anything. I will record you. And I’ll learn…I did it with every music that I could possibly be in contact with.”

It was that very determination to take opportunities that landed Don at the forefront of DC’s punk movement, recording influential bands like Fugazi and Bad Brains, mainly because in many cases he was the only one who would. “No one would want to book a show with the punks,” he says. “I mean, they destroy things, they break things up, there’re fights and all kinds of other stuff. There’s blood all over the floor. And, as a matter of fact, when the Bad Brains were first here recording, [a friend] said, ‘Hey, why don’t you record these guys?’ And me, I don’t want to touch them. You know, they scare me. So I said, ‘Well hey, I’ll record them.’ You know, just anybody. I’ll record them. Like I said, I’ll record anything…These were sort of musical outcasts at the time, [but] today’s outcasts are tomorrow’s trendsetters.”

Don recalls that in the early days of the movement, he was recording bands using a mixing board he built himself, and the gear was subpar at best. But in his mind, it was all serendipitous. “At the time, everything lined up,” he says. “The fact that I wasn’t using the best equipment, but the punks’ music really didn’t count on having utmost fidelity. As a matter of fact, what they wanted was the experience in the moment, just capturing the moment. And that was something that I could give them…It’s surprising, it’s gratifying. I’m very proud of it. I feel… you know, I definitely embrace being part of it.”

Nowadays, Don still operates Inner Ear, the studio that helped start it all, taking on a wide range of different clients. (Like he says, he’ll record anything.) As a mentor for the Recording Connection, he also gets a kick out of involving his students in the process. “I try to pass on some of my bad habits,” he jokes. “I just enjoy showing people what I know because I don’t see any purpose in hiding any of it…You know, they want to get into the business, and you can tell that they enjoy it. They think it’s fun, and it is fun. I don’t know of any other profession that kind of gets that kind of emotional reaction from people.”

He’s also careful to mention that he’s not quick to judge which of his students are going to make it, and which are not. He says it’s basically up to them. “One of the things that I tell my students,” he says, “and this is one of the reasons why it’s tough to tell who’s going to do well in the future, is that persistence and patience are the prime ingredients if you’re gonna do anything in the arts. And I consider engineering something in the arts, too, just as music is. And I tell the musicians this, I tell the engineers this. I mean, if you want to do something, you’ve got to keep doing it. The musicians I know that have at least had mild success are the ones that kept at it.”

As for Don? After nearly 40 years in the music industry, he’s showing no signs of slowing down. But remember, he didn’t take aim at a career in the music industry—he landed in it by taking opportunities when they came his way. So don’t pin him down to doing this for the rest of his life. “I believe, quite frankly, that’s something that’s never dawned on me,” says Don. “At any moment, I expect to delve into painting and print making. The moment hasn’t come yet.”

Nowadays, Don still operates Inner Ear, the studio that helped start it all, taking on a wide range of different clients. (Like he says, he’ll record anything.) As a mentor for the Recording Connection, he also gets a kick out of involving his students in the process. “I try to pass on some of my bad habits,” he jokes. “I just enjoy showing people what I know because I don’t see any purpose in hiding any of it…You know, they want to get into the business, and you can tell that they enjoy it. They think it’s fun, and it is fun. I don’t know of any other profession that kind of gets that kind of emotional reaction from people.”

He’s also careful to mention that he’s not quick to judge which of his students are going to make it, and which are not. He says it’s basically up to them. “One of the things that I tell my students,” he says, “and this is one of the reasons why it’s tough to tell who’s going to do well in the future, is that persistence and patience are the prime ingredients if you’re gonna do anything in the arts. And I consider engineering something in the arts, too, just as music is. And I tell the musicians this, I tell the engineers this. I mean, if you want to do something, you’ve got to keep doing it. The musicians I know that have at least had mild success are the ones that kept at it.”

As for Don? After nearly 40 years in the music industry, he’s showing no signs of slowing down. But remember, he didn’t take aim at a career in the music industry—he landed in it by taking opportunities when they came his way. So don’t pin him down to doing this for the rest of his life. “I believe, quite frankly, that’s something that’s never dawned on me,” says Don. “At any moment, I expect to delve into painting and print making. The moment hasn’t come yet.”

Film Connection apprentice Sophie Rose Bellin (Portland, OR) recently spent the week on the set of a film shoot, learning how to “paint with light” using screens, fog machines, and fabric. Besides C-Stands and Stingers, Sophie loves seeing the way people come together on set when obstacles arise.

Film Connection apprentice Sophie Rose Bellin (Portland, OR) recently spent the week on the set of a film shoot, learning how to “paint with light” using screens, fog machines, and fabric. Besides C-Stands and Stingers, Sophie loves seeing the way people come together on set when obstacles arise.

Liz Faux, a recent graduate of the Radio Connection, recorded her own DJ show at WMMR in Philadelphia, PA! She handled everything from the script, to the recording and editing. She says, “I’m really happy with how it turned out, and I hope to recieve good feedback from it. Now I will start putting together a résumé and trying to find my first real job!”

Liz Faux, a recent graduate of the Radio Connection, recorded her own DJ show at WMMR in Philadelphia, PA! She handled everything from the script, to the recording and editing. She says, “I’m really happy with how it turned out, and I hope to recieve good feedback from it. Now I will start putting together a résumé and trying to find my first real job!”

Paul Ramirez, Recording Connection apprentice in Tuscon, AZ, is all about the music, music and more music. After sitting in on a mixing session with his mentor, Jim Pavett, Paul stayed late at the studio to work on his own metal mix. “Man, this mix has been my BEST!” he reports.

Paul Ramirez, Recording Connection apprentice in Tuscon, AZ, is all about the music, music and more music. After sitting in on a mixing session with his mentor, Jim Pavett, Paul stayed late at the studio to work on his own metal mix. “Man, this mix has been my BEST!” he reports.

Spend a few minutes talking with Film Connection graduate Mark Doster, and you’ll soon hear about his passion for film, particularly in the horror and suspense genres. Inspired by such directors as Brian DePalma, John Carpenter and Dario Argento, he also has some specific ideas about what makes for the best scary moments in film—and it isn’t those obvious moments that startle the audience.

“I always think about Hitchcock’s , ‘It’s not in the bang, but the anticipation of the bang,'” he says. “People don’t really get that anymore, and I want to, kind of try to bring that back. I don’t like jump scares. Instead of having a clown pop in front of my face, I would love to watch it creep down the hallway slowly towards me and I can’t move.”

Spend a few minutes talking with Film Connection graduate Mark Doster, and you’ll soon hear about his passion for film, particularly in the horror and suspense genres. Inspired by such directors as Brian DePalma, John Carpenter and Dario Argento, he also has some specific ideas about what makes for the best scary moments in film—and it isn’t those obvious moments that startle the audience.

“I always think about Hitchcock’s , ‘It’s not in the bang, but the anticipation of the bang,'” he says. “People don’t really get that anymore, and I want to, kind of try to bring that back. I don’t like jump scares. Instead of having a clown pop in front of my face, I would love to watch it creep down the hallway slowly towards me and I can’t move.”

For anyone who knows Mark, it’s no surprise that he is aggressively pursuing a career as a film director. “Movies were my friends,” he says, reflecting back on his childhood. “I watched them repeatedly and would always decipher what I liked, what I didn’t like, why I liked it. And I always had my favorite directors. I followed directors even when I was really young. And I thought that was normal, but apparently it was weird because nobody else knew directors’ names.”

That passion recently resulted in Mark winning the coveted Award of Merit from the Accolade Global Film Competition for his suspense/horror short film Rest Your Soul, a film he says was inspired by real-life events.

“I was walking dogs,” says Mark. “I had the address for a dog…I went in the house, and there was caution tape on the basement [door]. And I remembered my boss saying, ‘Do not go in the basement, whatever you do.’ So it just seemed to me like walking into the wrong house, something’s possibly hidden in the house that the owner doesn’t want you to see…So “Rest Your Soul” was a restless student that gets that dog job, walks into the wrong house, and he becomes trapped in there with a killer when he finds the victim in a room instead of the dog that he’s looking for.”

For anyone who knows Mark, it’s no surprise that he is aggressively pursuing a career as a film director. “Movies were my friends,” he says, reflecting back on his childhood. “I watched them repeatedly and would always decipher what I liked, what I didn’t like, why I liked it. And I always had my favorite directors. I followed directors even when I was really young. And I thought that was normal, but apparently it was weird because nobody else knew directors’ names.”

That passion recently resulted in Mark winning the coveted Award of Merit from the Accolade Global Film Competition for his suspense/horror short film Rest Your Soul, a film he says was inspired by real-life events.

“I was walking dogs,” says Mark. “I had the address for a dog…I went in the house, and there was caution tape on the basement [door]. And I remembered my boss saying, ‘Do not go in the basement, whatever you do.’ So it just seemed to me like walking into the wrong house, something’s possibly hidden in the house that the owner doesn’t want you to see…So “Rest Your Soul” was a restless student that gets that dog job, walks into the wrong house, and he becomes trapped in there with a killer when he finds the victim in a room instead of the dog that he’s looking for.”

As it turns out, Mark has a unique perspective on the best ways to learn the filmmaking craft, as his passion led him to pursue a film education from a number of different angles. When he found the Film Connection, he was already enrolled as a student at Colorado Film School in Denver, CO, but found his education lacking in some ways. “I don’t really do well in a giant class setting,” he says. “I like one-on-one collaborations.”

For Mark, apprenticing on-the-job provided the real-world experience he wasn’t getting in traditional film school. “Film sets don’t really run like schools will tell you,” says Mark. “You have to go see it for yourself. And the production side of things—Film Connection elaborated on that a lot more, the business side, and how serious it is.”

Mark apprenticed under two mentors with the Film Connection: locally in Denver with filmmaker Johnny Fisher, with remote support on screenwriting from Richard Brandes in Los Angeles. “[Johnny] was pretty good at effects,” says Mark of his Denver mentor. “It was nice to have somebody to go see physically, with equipment, and actually have them talking to just you and not a whole classroom.”

As it turns out, Mark has a unique perspective on the best ways to learn the filmmaking craft, as his passion led him to pursue a film education from a number of different angles. When he found the Film Connection, he was already enrolled as a student at Colorado Film School in Denver, CO, but found his education lacking in some ways. “I don’t really do well in a giant class setting,” he says. “I like one-on-one collaborations.”

For Mark, apprenticing on-the-job provided the real-world experience he wasn’t getting in traditional film school. “Film sets don’t really run like schools will tell you,” says Mark. “You have to go see it for yourself. And the production side of things—Film Connection elaborated on that a lot more, the business side, and how serious it is.”

Mark apprenticed under two mentors with the Film Connection: locally in Denver with filmmaker Johnny Fisher, with remote support on screenwriting from Richard Brandes in Los Angeles. “[Johnny] was pretty good at effects,” says Mark of his Denver mentor. “It was nice to have somebody to go see physically, with equipment, and actually have them talking to just you and not a whole classroom.”

With Brandes, his screenwriting mentor, Mark found a particular connection. “He would read my script, and we would talk about it every time,” Mark recalls. “Like every act I wrote. And then we would get nerdy and talk about old movies and how stupid movies are getting, and this and that.”

Now living in Orlando, Florida, on the heels of his success with Rest Your Soul, Mark is currently working on two original screenplays and is making preparations to turn at least one of them into a feature film—a daunting task, but one that Mark is determined to make happen. He continues to stay in contact with Brandes when he has questions, and he says his former mentor is encouraging him to press forward. “I’ve been telling him what’s going on and about the budget for this new feature, how crazy it is,” says Mark. He’s like, ‘Well, I’ve done it before…You can, too.'”

***You can check out Mark Doster’s film Rest Your Soul in its entirety in the “Apprentice Media” section below!

With Brandes, his screenwriting mentor, Mark found a particular connection. “He would read my script, and we would talk about it every time,” Mark recalls. “Like every act I wrote. And then we would get nerdy and talk about old movies and how stupid movies are getting, and this and that.”

Now living in Orlando, Florida, on the heels of his success with Rest Your Soul, Mark is currently working on two original screenplays and is making preparations to turn at least one of them into a feature film—a daunting task, but one that Mark is determined to make happen. He continues to stay in contact with Brandes when he has questions, and he says his former mentor is encouraging him to press forward. “I’ve been telling him what’s going on and about the budget for this new feature, how crazy it is,” says Mark. He’s like, ‘Well, I’ve done it before…You can, too.'”

***You can check out Mark Doster’s film Rest Your Soul in its entirety in the “Apprentice Media” section below!

The Pensado’s Place “Capital Jam” was a rip-roaring success, and Recording Connection was glad to support Pensado’s Place’s time in D.C.

On Saturday, April 18, 2015, Pensado’s Place, the acclaimed weekly web series known as the most influential show for engineers, mixers and producers, and its co-hosts Herb Trawick and Dave Pensado, in cooperation with The Recording Academy®’s Washington D.C. Chapter and the Producers & Engineers Wing®, as well as Studio202DC, descended on the nation’s capital to hold their first ever “Capital Jam” — a free roundtable discussion and music event. Hundreds of aspiring engineers and producers came from all over the world and filled the venue – and throughout the event, Dave and Herb give shout-outs to long-time Pensado’s Place supporters Recording Connection.

Our very own mentor Yudu Gray of the phenomenal House Studios D.C. was on hand to represent Recording Connection and to shake hands with potential future apprentices (you guys know who you are).

During the event, Herb gave some sage advice in regards to how one should properly prepare for their interview with their potential mentor. “You have to be on top of your game and fully prepared for this interview, because if you are accepted, and become the mentor’s apprentice, it can change your life. You have to get your game face on, and be totally in the moment.”

The Pensado’s Place “Capital Jam” was a rip-roaring success, and Recording Connection was glad to support Pensado’s Place’s time in D.C.

On Saturday, April 18, 2015, Pensado’s Place, the acclaimed weekly web series known as the most influential show for engineers, mixers and producers, and its co-hosts Herb Trawick and Dave Pensado, in cooperation with The Recording Academy®’s Washington D.C. Chapter and the Producers & Engineers Wing®, as well as Studio202DC, descended on the nation’s capital to hold their first ever “Capital Jam” — a free roundtable discussion and music event. Hundreds of aspiring engineers and producers came from all over the world and filled the venue – and throughout the event, Dave and Herb give shout-outs to long-time Pensado’s Place supporters Recording Connection.

Our very own mentor Yudu Gray of the phenomenal House Studios D.C. was on hand to represent Recording Connection and to shake hands with potential future apprentices (you guys know who you are).

During the event, Herb gave some sage advice in regards to how one should properly prepare for their interview with their potential mentor. “You have to be on top of your game and fully prepared for this interview, because if you are accepted, and become the mentor’s apprentice, it can change your life. You have to get your game face on, and be totally in the moment.”

And Herb was not the only industry leader giving advice to the next generation of recording professionals. “Please, have some manners and have some conversational skills,” stated panelist Kuk Harrell (Beyoncé, Rihanna, Shakira). “You need to really focus on always having ‘old school’ communication, really having an engaging conversation. This is a people business. You got to talk. You got to open your mouth.”

Back in Los Angeles, Record Connection’s Brian Kraft built on the sentiments of those in attendance at the Pensado Capital Jam, adding, “You want a career in music? You want a career in audio engineering? Then prepare for it. Do everything you can to give the best and truest impression of who you are. Share your goals. Tell your mentor what you want to do. They want to know about your passions, your drive, your dedication.” Learn more about the RC interview process.

Thanks to legendary mixer Dave Pensado and co-host Herb Trawick: Ann Mincieli (Alicia Keys, Pharrell Williams, Amazing Spider Man 2), Gavin Lurssen (Alison Krauss, T Bone Burnett), Young Guru (Jay Z, Kanye West), Derek Ali (Kendrick Lamar, Schoolboy Q), Kuk Harrell (Rihanna, Beyoncé, Shakira), Michael Brauer (Coldplay, Calle 13, John Mayer), and Noah “40” Shebib (Drake, Nas, Sade).

Let’s do it again, shall we?

And Herb was not the only industry leader giving advice to the next generation of recording professionals. “Please, have some manners and have some conversational skills,” stated panelist Kuk Harrell (Beyoncé, Rihanna, Shakira). “You need to really focus on always having ‘old school’ communication, really having an engaging conversation. This is a people business. You got to talk. You got to open your mouth.”

Back in Los Angeles, Record Connection’s Brian Kraft built on the sentiments of those in attendance at the Pensado Capital Jam, adding, “You want a career in music? You want a career in audio engineering? Then prepare for it. Do everything you can to give the best and truest impression of who you are. Share your goals. Tell your mentor what you want to do. They want to know about your passions, your drive, your dedication.” Learn more about the RC interview process.

Thanks to legendary mixer Dave Pensado and co-host Herb Trawick: Ann Mincieli (Alicia Keys, Pharrell Williams, Amazing Spider Man 2), Gavin Lurssen (Alison Krauss, T Bone Burnett), Young Guru (Jay Z, Kanye West), Derek Ali (Kendrick Lamar, Schoolboy Q), Kuk Harrell (Rihanna, Beyoncé, Shakira), Michael Brauer (Coldplay, Calle 13, John Mayer), and Noah “40” Shebib (Drake, Nas, Sade).

Let’s do it again, shall we?

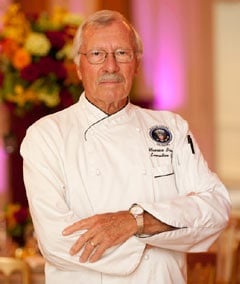

“I think it is about time that this approach to culinary education came to the United States. I started in an apprenticeship in France when I was 14 years old. I had no formal culinary school training. Apprenticeship programs were the only thing offered and I feel that they’re the best way to go.”

— Maurice Brazier retired Chef (formerly of Le Méridien Etoile in Paris)

“I think it is about time that this approach to culinary education came to the United States. I started in an apprenticeship in France when I was 14 years old. I had no formal culinary school training. Apprenticeship programs were the only thing offered and I feel that they’re the best way to go.”

— Maurice Brazier retired Chef (formerly of Le Méridien Etoile in Paris)

We’re happy and honored to announce that we’ll be a sponsor at the 18th Annual AudioMasters Benefit Golf Tournament, taking place May 14 and 15 at the Harpeth Hills Golf Course in Nashville, Tennessee. The two-day golf event benefits the Nashville Engineer Relief Fund, established by the Nashville section of the Audio Engineering Society (AES), to provide financial relief and assistance to Nashville’s audio engineers in the event of a medical or life crisis.

On Thursday, May 14, our very own Brian Kraft and the Recording Connection Sound Girls will be at Hole 8 to provide refreshments and wash player’s golf balls while checking in with our talented friends in Nashville’s audio community. See you on the links!

We’re happy and honored to announce that we’ll be a sponsor at the 18th Annual AudioMasters Benefit Golf Tournament, taking place May 14 and 15 at the Harpeth Hills Golf Course in Nashville, Tennessee. The two-day golf event benefits the Nashville Engineer Relief Fund, established by the Nashville section of the Audio Engineering Society (AES), to provide financial relief and assistance to Nashville’s audio engineers in the event of a medical or life crisis.

On Thursday, May 14, our very own Brian Kraft and the Recording Connection Sound Girls will be at Hole 8 to provide refreshments and wash player’s golf balls while checking in with our talented friends in Nashville’s audio community. See you on the links!

RRFC is education upgraded for the 21st century.

Get the latest career advice, insider production tips, and more!

Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Stay in the Loop: Subscribe for RRFC news & updates!

© 2025 Recording Radio Film Connection & CASA Schools. All Rights Reserved.