Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Issue #50

by L. Swift and Jeff McQ

The Recording Connection placed Brian as an apprentice with composer/engineer Dick Orr at John Wagner Studios in Albuquerque, NM. Since starting his apprenticeship, Brian has already been immersed in a wide range of projects, although he says Dick personalizes the instruction to his interests.

“He really works on just about everything,” says Brian. “If he sees there’s something that I have an interest in more than just what the curriculum is going over at the time, then he’ll spend some time with me on that, keeping my interest…It’s really a pleasure, honestly, just to be mentored by him.”

Brian says his focus is on electronic styles of music ranging from electro to house to dubstep, and he’s impressed that even though the studio leans toward other musical styles, Dick takes his musical interests in stride. “He’s around all kinds of music so it’s not a shocker to him.” Even so, for a guy whose EDM style is typically centered on samples and “in-the-box” computer plug-ins, Brian says being in the studio has greatly expanded his perspective.

“I have seen the foundation of recording, the process and stuff like that, but I never have seen it in-depth in the studio,” he says. “Now I’m always thinking about the space where [something] was recorded. You can even hear some of the ambience in the background to give you, actually, a good picture in your head of where that was recorded, how it was recorded, if they used a couple of microphones, whether it be mono or stereo. It’s really interesting.”

The Recording Connection placed Brian as an apprentice with composer/engineer Dick Orr at John Wagner Studios in Albuquerque, NM. Since starting his apprenticeship, Brian has already been immersed in a wide range of projects, although he says Dick personalizes the instruction to his interests.

“He really works on just about everything,” says Brian. “If he sees there’s something that I have an interest in more than just what the curriculum is going over at the time, then he’ll spend some time with me on that, keeping my interest…It’s really a pleasure, honestly, just to be mentored by him.”

Brian says his focus is on electronic styles of music ranging from electro to house to dubstep, and he’s impressed that even though the studio leans toward other musical styles, Dick takes his musical interests in stride. “He’s around all kinds of music so it’s not a shocker to him.” Even so, for a guy whose EDM style is typically centered on samples and “in-the-box” computer plug-ins, Brian says being in the studio has greatly expanded his perspective.

“I have seen the foundation of recording, the process and stuff like that, but I never have seen it in-depth in the studio,” he says. “Now I’m always thinking about the space where [something] was recorded. You can even hear some of the ambience in the background to give you, actually, a good picture in your head of where that was recorded, how it was recorded, if they used a couple of microphones, whether it be mono or stereo. It’s really interesting.”

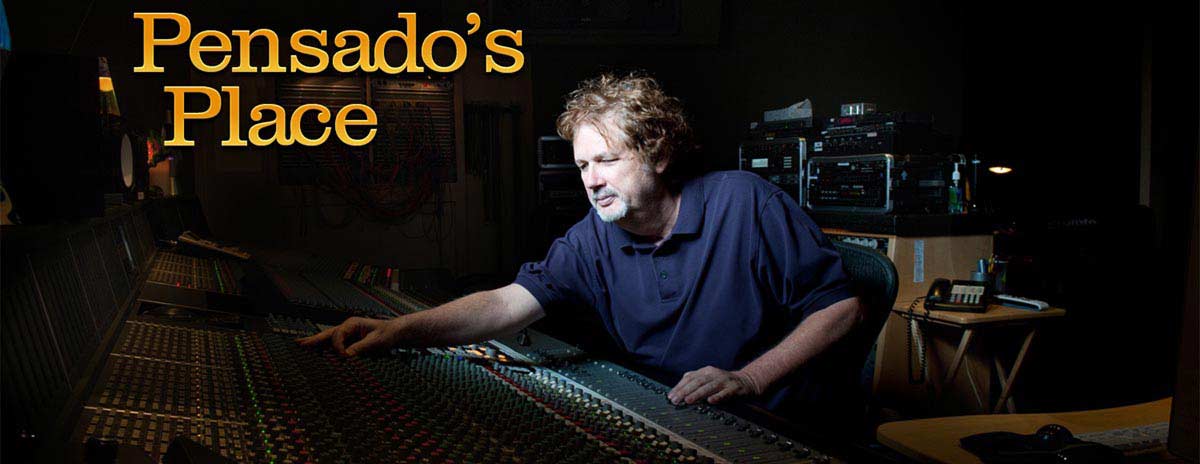

Pensado’s Place is an informative and instructional YouTube program for audio engineers and music producers, hosted by Grammy-winning engineer Dave Pensado and Herb Trawick, and featuring interviews and advice from top-shelf music industry professionals. A long-time partner with the Recording Connection, Pensado’s Place has provided full-ride scholarships for multiple students to apprentice in real recording studios through the Recording Connection program.

“One of the greatest pleasures Herb and I have is the opportunity to educate,” says Dave. “The fact that we can partner with shops like Recording Connection, offer Pensado’s Place Scholarships and then watch the recipient grow and succeed makes it all worthwhile.”

As for Brian Zadel, he’s been making the most of the opportunity, diving in with both feet. “I know by the end of the program, I’m going to have a vast amount of knowledge that I didn’t have, not even a year ago,” he says. “I’m just glad to be a little lucky and I’m glad I took that chance.”

Brian’s advice to other apprentices? “Listen, take notes…write it down, go back to it and let it sink in, and practice, practice, practice, practice. That’s all you should be doing outside of class.”

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

Pensado’s Place is an informative and instructional YouTube program for audio engineers and music producers, hosted by Grammy-winning engineer Dave Pensado and Herb Trawick, and featuring interviews and advice from top-shelf music industry professionals. A long-time partner with the Recording Connection, Pensado’s Place has provided full-ride scholarships for multiple students to apprentice in real recording studios through the Recording Connection program.

“One of the greatest pleasures Herb and I have is the opportunity to educate,” says Dave. “The fact that we can partner with shops like Recording Connection, offer Pensado’s Place Scholarships and then watch the recipient grow and succeed makes it all worthwhile.”

As for Brian Zadel, he’s been making the most of the opportunity, diving in with both feet. “I know by the end of the program, I’m going to have a vast amount of knowledge that I didn’t have, not even a year ago,” he says. “I’m just glad to be a little lucky and I’m glad I took that chance.”

Brian’s advice to other apprentices? “Listen, take notes…write it down, go back to it and let it sink in, and practice, practice, practice, practice. That’s all you should be doing outside of class.”

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

Brian Kraft, Shevy Shovlin (Headroom for Days) and the Recording Connection’s marketing team will be on site at The NAMM Show 2015, January 22-26, to meet and interface with top professional audio and MI manufacturers, as well as leading artists, engineers and producers.

Brian is looking forward to discussing Recording Connection opportunities with current, future, and potential partners — those manufacturers and industry personalities looking to make a positive impact on the next generation of audio engineers and producers. Brian will also be attending several VIP events.

Stay tuned for NAMM highlights in next week’s newsletter!

Brian Kraft, Shevy Shovlin (Headroom for Days) and the Recording Connection’s marketing team will be on site at The NAMM Show 2015, January 22-26, to meet and interface with top professional audio and MI manufacturers, as well as leading artists, engineers and producers.

Brian is looking forward to discussing Recording Connection opportunities with current, future, and potential partners — those manufacturers and industry personalities looking to make a positive impact on the next generation of audio engineers and producers. Brian will also be attending several VIP events.

Stay tuned for NAMM highlights in next week’s newsletter!

At RRF we believe the greatest wisdom in the world benefits no one if it is not shared and made useful.

We work hard to stay on the cutting-edge of mentor-led education. The more we know about YOU, the better equipped we are to create the tools that will help you hone your craft and break you in to the industry you want to work in!

Please help us continue in our mission by taking the survey found here.

At RRF we believe the greatest wisdom in the world benefits no one if it is not shared and made useful.

We work hard to stay on the cutting-edge of mentor-led education. The more we know about YOU, the better equipped we are to create the tools that will help you hone your craft and break you in to the industry you want to work in!

Please help us continue in our mission by taking the survey found here.

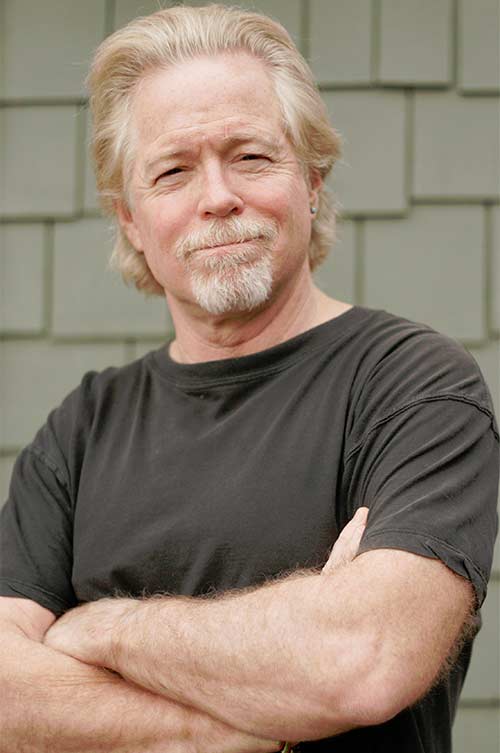

Ron Osborn: Well, it’s funny: I didn’t. I went to art school. I was going to be an illustrator, and I had to take an advertising class and I had to do a film assignment, and I handled the camera for the first time…it was just kind of an amazing experience. So I then switched my major and took all the film classes I could at the school that I went to. And then, very late in the game, I really discovered writing… And they really didn’t teach it at this school, [but] I realized that’s where filmmaking really happens. It’s really about the idea and the content. So I graduated and started all over and took classes and read books and read scripts, and spent the next five years learning writing basically. That’s how I got in.

RRF: How did you connect with the industry when you were first starting out? Did you have a mentor or anyone that acted as a mentor or guide for you?

Ron: I had to go the same slogging slow route that many people do, which is to write a spec, send it out to agents, get an agent to respond finally, and it was a long, slow process. There was no short cut for me.

RRF: You’ve been working in the business for a while now, but can you pinpoint a moment where you said, “Okay, this is what I’m doing for the rest of my life”?

Ron: It would’ve been about ’86, after being in the business for six years. I had never been on a show more than two years in a row. I was on Mork & Mindy, my first job, and much of the staff was let go because they wanted to go in a new direction the next season. I then was on a top 10 show called Too Close for Comfort… [then] Night Court, … then landed on Moonlighting, which became a phenomenon, but it didn’t start out as one. That was the most dysfunctionally run show in the history of the cathode ray tube. It got very rocky, very rocky going, but that was the first show where I was hired back. I stayed for two seasons and then a third one. And that’s when I began to realize that late in the game, having been doing this now for six years, I may have a future in this…Even though the show was still badly run, I felt like, ‘Okay, I know what it takes to stay in this business.’

Ron Osborn: Well, it’s funny: I didn’t. I went to art school. I was going to be an illustrator, and I had to take an advertising class and I had to do a film assignment, and I handled the camera for the first time…it was just kind of an amazing experience. So I then switched my major and took all the film classes I could at the school that I went to. And then, very late in the game, I really discovered writing… And they really didn’t teach it at this school, [but] I realized that’s where filmmaking really happens. It’s really about the idea and the content. So I graduated and started all over and took classes and read books and read scripts, and spent the next five years learning writing basically. That’s how I got in.

RRF: How did you connect with the industry when you were first starting out? Did you have a mentor or anyone that acted as a mentor or guide for you?

Ron: I had to go the same slogging slow route that many people do, which is to write a spec, send it out to agents, get an agent to respond finally, and it was a long, slow process. There was no short cut for me.

RRF: You’ve been working in the business for a while now, but can you pinpoint a moment where you said, “Okay, this is what I’m doing for the rest of my life”?

Ron: It would’ve been about ’86, after being in the business for six years. I had never been on a show more than two years in a row. I was on Mork & Mindy, my first job, and much of the staff was let go because they wanted to go in a new direction the next season. I then was on a top 10 show called Too Close for Comfort… [then] Night Court, … then landed on Moonlighting, which became a phenomenon, but it didn’t start out as one. That was the most dysfunctionally run show in the history of the cathode ray tube. It got very rocky, very rocky going, but that was the first show where I was hired back. I stayed for two seasons and then a third one. And that’s when I began to realize that late in the game, having been doing this now for six years, I may have a future in this…Even though the show was still badly run, I felt like, ‘Okay, I know what it takes to stay in this business.’

RRF: Yeah, there was a lot of door slamming on Moonlighting.

Ron: Yeah, yeah. “Good, good. Fine, fine. Slam, slam.” Yeah. I just wrote.

RRF: And then, there was Duckman.

Ron: God love you, my favorite show.

RRF: Do you think that it was ahead of its time? I mean, if you look now and you look at BoJack Horseman, and you look at all these other kind of shows where they mix these troubled cartoon characters with sex and drugs and regular life, it seems like Duckman was about 20 years ahead of the curve.

Ron: I didn’t necessarily think so then. Looking back on it, I suppose it was by design that we were ahead of its time. We didn’t feel like it then. We were just doing the funniest show we knew how to do. We were all very big Simpsons fans—we stood on the shoulders of The Simpsons, I think. They definitely paved the way…South Park would come after us about a year, two years later. We were already killing off a character, or characters, every week and fluffing in Uranus, you know, for instance. But we were on a network that didn’t quite know what it had, and left us alone. And we were willing to get away with as much murder as we could, while we could, and that’s what we did.

RRF: Writers sometimes speak with a certain disdain for executives. Do you think the hurdles hurt your art when you’re trying to write something and have to deal with certain standards and practices? Does it drain you as a writer to have to keep up with that?

Ron: No; you know what you’re selling, and the network largely knows what it’s buying. So if you find yourself in a situation where every week it’s a pitched battle between content and execution, someone sold something wrong. … But the network ultimately is your partner.

One time I got the greatest phone call . . . We had to call in to USA [Network] back in New York for some reason, and the secretary who answered the phone asked who it was, and we said, “Ron Osborn and Jeff Reno for such-and-such executive.” And she had to say, “I have to tell you we look forward here to the scripts that come in, and after the scripts are copied and distributed, and sent down the hall, you begin to hear laughter as people are reading them and getting to the same jokes.” And that was just the coolest thing to hear.

RRF: So how have you enjoyed being a mentor in the Film Connection program?

Ron: To be honest with you, it’s kind of a selfish relationship. I teach and mentor so that I get something back. I learn. You should always be learning in this. If you’re not, you become a hack. And one of the ways that I learn is in teaching or mentoring individuals, because you have to deal with a specific challenge, or challenges, every week.

RRF: So the relationship of a mentor and apprentice allows you to challenge yourself as much as teach?

Ron: Exactly, yeah. If there’s a problem that that student can’t solve, and I can’t solve it, I obsess over it. I’ll be thinking about it on my drive time. I might be working on a show, but I’m so anxious and determined to solve that problem in an imaginative way. There’s a great quote from Einstein…”Imagination is more important than knowledge.” And that’s true of what we do here. Everything knowledge-wise can be researched. You have assistants, Wikipedia, and everything else. Storytelling comes down to imagination. So in teaching, you’re trying to teach imagination, imaginatively. And that keeps you sharp. It keeps me sharp, anyway. That’s the reason I do it. If it didn’t, I’d quit.

RRF: Yeah, there was a lot of door slamming on Moonlighting.

Ron: Yeah, yeah. “Good, good. Fine, fine. Slam, slam.” Yeah. I just wrote.

RRF: And then, there was Duckman.

Ron: God love you, my favorite show.

RRF: Do you think that it was ahead of its time? I mean, if you look now and you look at BoJack Horseman, and you look at all these other kind of shows where they mix these troubled cartoon characters with sex and drugs and regular life, it seems like Duckman was about 20 years ahead of the curve.

Ron: I didn’t necessarily think so then. Looking back on it, I suppose it was by design that we were ahead of its time. We didn’t feel like it then. We were just doing the funniest show we knew how to do. We were all very big Simpsons fans—we stood on the shoulders of The Simpsons, I think. They definitely paved the way…South Park would come after us about a year, two years later. We were already killing off a character, or characters, every week and fluffing in Uranus, you know, for instance. But we were on a network that didn’t quite know what it had, and left us alone. And we were willing to get away with as much murder as we could, while we could, and that’s what we did.

RRF: Writers sometimes speak with a certain disdain for executives. Do you think the hurdles hurt your art when you’re trying to write something and have to deal with certain standards and practices? Does it drain you as a writer to have to keep up with that?

Ron: No; you know what you’re selling, and the network largely knows what it’s buying. So if you find yourself in a situation where every week it’s a pitched battle between content and execution, someone sold something wrong. … But the network ultimately is your partner.

One time I got the greatest phone call . . . We had to call in to USA [Network] back in New York for some reason, and the secretary who answered the phone asked who it was, and we said, “Ron Osborn and Jeff Reno for such-and-such executive.” And she had to say, “I have to tell you we look forward here to the scripts that come in, and after the scripts are copied and distributed, and sent down the hall, you begin to hear laughter as people are reading them and getting to the same jokes.” And that was just the coolest thing to hear.

RRF: So how have you enjoyed being a mentor in the Film Connection program?

Ron: To be honest with you, it’s kind of a selfish relationship. I teach and mentor so that I get something back. I learn. You should always be learning in this. If you’re not, you become a hack. And one of the ways that I learn is in teaching or mentoring individuals, because you have to deal with a specific challenge, or challenges, every week.

RRF: So the relationship of a mentor and apprentice allows you to challenge yourself as much as teach?

Ron: Exactly, yeah. If there’s a problem that that student can’t solve, and I can’t solve it, I obsess over it. I’ll be thinking about it on my drive time. I might be working on a show, but I’m so anxious and determined to solve that problem in an imaginative way. There’s a great quote from Einstein…”Imagination is more important than knowledge.” And that’s true of what we do here. Everything knowledge-wise can be researched. You have assistants, Wikipedia, and everything else. Storytelling comes down to imagination. So in teaching, you’re trying to teach imagination, imaginatively. And that keeps you sharp. It keeps me sharp, anyway. That’s the reason I do it. If it didn’t, I’d quit.

RRFC is education upgraded for the 21st century.

Get the latest career advice, insider production tips, and more!

Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Stay in the Loop: Subscribe for RRFC news & updates!

© 2025 Recording Radio Film Connection & CASA Schools. All Rights Reserved.