Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Issue #201

by Liya Swift

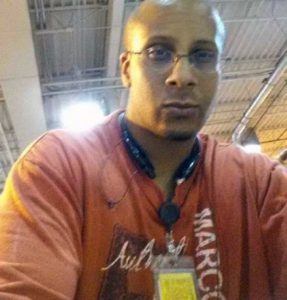

RRFC: So what led you to Recording Connection in the first place?

Diego: I wanted to be happy with what I was going to be doing for the rest of my life. So, started looking into things and Recording Connection just seemed like a really attractive opportunity to me, the way they put you right there in the thick of it, really hands-on, which is how I like to learn. Yeah, and shortly after that, I enrolled, and ended up finding a great studio in my hometown to be an apprentice at.

RRFC: How did it go the first time you met Matt and interviewed at the studio?

Diego: I walked in and he was super chill. We talked about our taste in music, what we liked… I told him I wanted to end up doing what he does, be an audio engineer, a kind of a jack-of-all-trades, [who can do] any genre, any task that somebody needs done in the audio world.

RRFC: During your externship would you say you were proactive? Did you come in more than the minimum amount of days?

Diego: I was there pretty much seven days a week…I would show up and just do anything I could do, whether it was wrapping up cables or putting away mic stands or setting-up mics, and even cleaning bathrooms. Just whatever needed to be done and just have him not ask me to do it, just take the initiative and go ahead and do it.

RRFC: What is it about working in music that appeals to you?

Diego: Ultimately, just the emotion that it evokes, you know? That’s ultimately what we’re trying to do at the end of the day is trying to get someone to relate to what’s being said or what’s being played on an instrument…relate to it, or find some sort of solace in it. That’s ultimately what attracted me to a career in music.

RRFC: Have any recent recording sessions to tell us about?

Diego: As far as projects I’m working on right now, there’s a guy by the name of Jay Anonymous. We just recorded and mixed his stuff. DZ Fresh, he’s got a mix tape coming out called “Fresca Bar Season.” Rico Freeman, we’re doing tracking for him… and I did some vocal tracking for a band called Operocia. They’ve got a project coming out that I’m really excited and happy to be a part of.

RRFC: We know Matt’s a big believer in trial by fire. Tell us about it.

Diego: Oh yeah. He definitely gives you the opportunity and he doesn’t baby you along the way. He lets you make your mistakes, because that’s the only way you’re going to learn. If you have someone there always correcting you, then you’re going to need them always there to correct you, but he kind of lets you, you know, make a mistake and figure it out from there, and realize what to correct from then on.

RRFC: Getting hired by Matt, how did it come about?

A vacancy opened up and Matt goes home at 5:00 to his family. So, there was a huge opportunity to capitalize on all the people that want to come in after 5:00…It’s cliché to say overnight, but it really was like, ‘Oh, I’m an engineer now!’ because one day, I just started doing sessions, like, scheduled a session by myself, and that’s how things kind of just went from then on out.

RRFC: When you were in the program, if you had questions, was Matt helpful in explaining things along the way?

Diego: Oh, yeah, absolutely. I would let him know on a weekly basis what I felt I needed to brush up on, and he was more than happy to take an hour out of his day and just, let me know, ‘Okay, this is how the signal flow works, this is how you hook up the patch bay, this is what the mic is connected to, this is…So, yeah, he was more than helpful in that aspect.

RRFC: Do you have any advice for Recording Connection students on how they can maximize opportunity while they train inside a professional recording studio?

Diego: Just do as much as possible, take the initiative. Basically show up until, you know, they tell you that you can’t show up, because that’s what I did and Matt never had a problem with it. …Yeah, and work on it as much at the house as at the studio. Like, it’s 24/7 kind of thing. When you got an end-goal like that in mind that’s all you have to be focused on. You know, you might be a boring person for a year or two, but it definitely does pay off.

RRFC: So, going back your first sessions flying solo at The Press, were you ever nervous?

Diego: Oh yeah, absolutely…My first session by myself, yeah, I was definitely very nervous, you know, sweaty palms and all that stuff.

RRFC: And how did the session turn out?

Diego: Turned out great. Client was happy with what we had done and I realized I was nervous for no reason. I was more than prepared for doing that session.

RRFC: So what led you to Recording Connection in the first place?

Diego: I wanted to be happy with what I was going to be doing for the rest of my life. So, started looking into things and Recording Connection just seemed like a really attractive opportunity to me, the way they put you right there in the thick of it, really hands-on, which is how I like to learn. Yeah, and shortly after that, I enrolled, and ended up finding a great studio in my hometown to be an apprentice at.

RRFC: How did it go the first time you met Matt and interviewed at the studio?

Diego: I walked in and he was super chill. We talked about our taste in music, what we liked… I told him I wanted to end up doing what he does, be an audio engineer, a kind of a jack-of-all-trades, [who can do] any genre, any task that somebody needs done in the audio world.

RRFC: During your externship would you say you were proactive? Did you come in more than the minimum amount of days?

Diego: I was there pretty much seven days a week…I would show up and just do anything I could do, whether it was wrapping up cables or putting away mic stands or setting-up mics, and even cleaning bathrooms. Just whatever needed to be done and just have him not ask me to do it, just take the initiative and go ahead and do it.

RRFC: What is it about working in music that appeals to you?

Diego: Ultimately, just the emotion that it evokes, you know? That’s ultimately what we’re trying to do at the end of the day is trying to get someone to relate to what’s being said or what’s being played on an instrument…relate to it, or find some sort of solace in it. That’s ultimately what attracted me to a career in music.

RRFC: Have any recent recording sessions to tell us about?

Diego: As far as projects I’m working on right now, there’s a guy by the name of Jay Anonymous. We just recorded and mixed his stuff. DZ Fresh, he’s got a mix tape coming out called “Fresca Bar Season.” Rico Freeman, we’re doing tracking for him… and I did some vocal tracking for a band called Operocia. They’ve got a project coming out that I’m really excited and happy to be a part of.

RRFC: We know Matt’s a big believer in trial by fire. Tell us about it.

Diego: Oh yeah. He definitely gives you the opportunity and he doesn’t baby you along the way. He lets you make your mistakes, because that’s the only way you’re going to learn. If you have someone there always correcting you, then you’re going to need them always there to correct you, but he kind of lets you, you know, make a mistake and figure it out from there, and realize what to correct from then on.

RRFC: Getting hired by Matt, how did it come about?

A vacancy opened up and Matt goes home at 5:00 to his family. So, there was a huge opportunity to capitalize on all the people that want to come in after 5:00…It’s cliché to say overnight, but it really was like, ‘Oh, I’m an engineer now!’ because one day, I just started doing sessions, like, scheduled a session by myself, and that’s how things kind of just went from then on out.

RRFC: When you were in the program, if you had questions, was Matt helpful in explaining things along the way?

Diego: Oh, yeah, absolutely. I would let him know on a weekly basis what I felt I needed to brush up on, and he was more than happy to take an hour out of his day and just, let me know, ‘Okay, this is how the signal flow works, this is how you hook up the patch bay, this is what the mic is connected to, this is…So, yeah, he was more than helpful in that aspect.

RRFC: Do you have any advice for Recording Connection students on how they can maximize opportunity while they train inside a professional recording studio?

Diego: Just do as much as possible, take the initiative. Basically show up until, you know, they tell you that you can’t show up, because that’s what I did and Matt never had a problem with it. …Yeah, and work on it as much at the house as at the studio. Like, it’s 24/7 kind of thing. When you got an end-goal like that in mind that’s all you have to be focused on. You know, you might be a boring person for a year or two, but it definitely does pay off.

RRFC: So, going back your first sessions flying solo at The Press, were you ever nervous?

Diego: Oh yeah, absolutely…My first session by myself, yeah, I was definitely very nervous, you know, sweaty palms and all that stuff.

RRFC: And how did the session turn out?

Diego: Turned out great. Client was happy with what we had done and I realized I was nervous for no reason. I was more than prepared for doing that session.

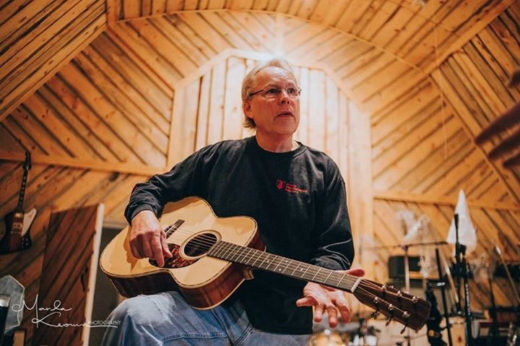

So much of what it takes to be a great audio engineer just can’t be learned from books. It takes doing it, seeing it, and talking about it with those who know. Geoff Gray, President of Far & Away Studios, Inc., (Bill Perry, Richie Furay, Sonny Sharrock, Cass Clayton, Brian Tarquin) understands the legacy of which he’s proud to be a part. Back in the early 70s, engineer Larry Alexander (David Bowie, Mary J. Blige, Bon Jovi, Eric Clapton) took Geoff under his wing and showed him the ins-and-outs of audio engineering and recording. And it was none other than the legendary Les Paul who solidified Geoff’s propensity to think outside of the box, ask questions, and consistently push the boundaries of what’s sonically possible.

As a Recording Connection mentor, Geoff is busy transmitting the wealth of knowledge he’s attained through working with the greats onto the next wave of audio engineers and producers, who will continue on with the legacy that’s come down from mentor to protégé, generation after generation.

For Geoff, it all started with a love of music and a fascination with sound. Such things were just a given in his home when he was growing up. His earliest memories include being “enamored with music and listening to Les Paul on the radio. My mother used to have AM radio on, and I think I was just attracted to the bizarre sounds that he was able to make by speeding things up and using echo… I was kind of infected at a really, really early age, like 5 or 6.”

Geoff went on to play guitar in bands throughout high school and college. Shortly after graduating with a degree in Fine Arts, then seen as a more practical option, he returned to his hometown in New City, New York, knowing his love for music hadn’t faded one bit. He walked into 914 Recording Studios with a friend who was working on a few radio commercials for Louis Lahav, who was then in the midst of recording Bruce Springsteen’s album, Born to Run. “I didn’t even know who Bruce was,” Geoff says laughing at his former naïveté.

Nevertheless, he knew he liked being in the studio and quickly “became hooked.” Having brought his band in to record at 914 Recording Studios, led up to the moment that sealed Geoff’s fate. This being the early 70s, recording to tape was nothing short of arduous. Mess it up and an entire song could be irreparably damaged:

“At one point we were doing a mix and Larry said ‘I kind of ran out of hands here. I need somebody to move these two faders at some point in the song. Geoff, do you know what the chorus is?’…So he hits record on the quarter inch machine and hits play on the two inch machine, and my heart rate must have been about 130 beats per minute! I was just so afraid of screwing this up in the presence of somebody as good as Larry Alexander. So we got to the chorus, I pushed the faders up, I pulled them down at the right point. I think I had to do it a of couple times in the song.

When the song was over, I was just completely exhausted. It was the most thrilling thing I had ever experienced in my life. At that point I realized that I shouldn’t be playing guitar on the other side of the glass: ‘I want to be doing this and I want to emulate Larry, I want to have Larry’s sense of humor, and I want to be at the helm of The Enterprise, and I think I could do that and be good at that, and not be a mediocre guitar player who’s going to have to have a day job.’”

In the years that followed, Geoff set himself on course to learn as much as he could from Larry. When he wasn’t working in the studio, he was researching various recording techniques, reading S.O.S. Magazine on his lunch breaks and basically living and breathing audio.

Fate stepped in a second time. Geoff met his second major life luminary when he ran an ad for a Gibson guitar he was selling. The phone rang and it was none other than Les Paul on the other line:

“He invited me to come to the house, and I was like, ‘This can’t be real,’ you know? It was before his career had kind of relaunched itself. So there was a big gap in time in there, probably like 1963 or 1964 up to the early 70s where Les was pretty much retired and not doing anything except inventing awesome things that I got to help work on and be part of when I was at his house.

Les taught me the solution to a problem is always the simplest one. If you distill it down to, here’s the issue, here’s what’s happening, here’s how you fix it. People tend to panic when something happens but that’s often not the smartest way to approach things. He had this mid-western mechanical aptitude for problem solving.”

When we ask Geoff to share his insight on what students need to do to make sure they’re “absorbing” as much as they can he says, “I love the word ‘absorbing.’ Absorbing is what all the students should be doing. The level of absorption is directly proportionate to your aptitude and desire to do this… I’d be at work, and at lunch I would be reading Sound on Sound Magazine or something, then I’d come back to the studio at night and I would try different ideas.”

Nowadays, Geoff takes mostly a hybridized approach that combines the best of analog and digital:

“We have a two inch tape machine and we’ve figured out a way that we can track through that and have it simultaneously go into Pro Tools, and then we selectively keep and reject what we don’t want. I mean, cymbals are really bright and kind of grainy and high-end-y, and digital makes that better, because it’s the nature of the beast. I don’t really need them warmed up. I want them to kind of slash through a big, fat kick that’s been recorded at plus six on a two inch machine. Now I’ve got the best of both worlds. I have the extremities of punch and sonics, you know, from one to the other… we also mix to half inch tape a lot of times.”

So much of what it takes to be a great audio engineer just can’t be learned from books. It takes doing it, seeing it, and talking about it with those who know. Geoff Gray, President of Far & Away Studios, Inc., (Bill Perry, Richie Furay, Sonny Sharrock, Cass Clayton, Brian Tarquin) understands the legacy of which he’s proud to be a part. Back in the early 70s, engineer Larry Alexander (David Bowie, Mary J. Blige, Bon Jovi, Eric Clapton) took Geoff under his wing and showed him the ins-and-outs of audio engineering and recording. And it was none other than the legendary Les Paul who solidified Geoff’s propensity to think outside of the box, ask questions, and consistently push the boundaries of what’s sonically possible.

As a Recording Connection mentor, Geoff is busy transmitting the wealth of knowledge he’s attained through working with the greats onto the next wave of audio engineers and producers, who will continue on with the legacy that’s come down from mentor to protégé, generation after generation.

For Geoff, it all started with a love of music and a fascination with sound. Such things were just a given in his home when he was growing up. His earliest memories include being “enamored with music and listening to Les Paul on the radio. My mother used to have AM radio on, and I think I was just attracted to the bizarre sounds that he was able to make by speeding things up and using echo… I was kind of infected at a really, really early age, like 5 or 6.”

Geoff went on to play guitar in bands throughout high school and college. Shortly after graduating with a degree in Fine Arts, then seen as a more practical option, he returned to his hometown in New City, New York, knowing his love for music hadn’t faded one bit. He walked into 914 Recording Studios with a friend who was working on a few radio commercials for Louis Lahav, who was then in the midst of recording Bruce Springsteen’s album, Born to Run. “I didn’t even know who Bruce was,” Geoff says laughing at his former naïveté.

Nevertheless, he knew he liked being in the studio and quickly “became hooked.” Having brought his band in to record at 914 Recording Studios, led up to the moment that sealed Geoff’s fate. This being the early 70s, recording to tape was nothing short of arduous. Mess it up and an entire song could be irreparably damaged:

“At one point we were doing a mix and Larry said ‘I kind of ran out of hands here. I need somebody to move these two faders at some point in the song. Geoff, do you know what the chorus is?’…So he hits record on the quarter inch machine and hits play on the two inch machine, and my heart rate must have been about 130 beats per minute! I was just so afraid of screwing this up in the presence of somebody as good as Larry Alexander. So we got to the chorus, I pushed the faders up, I pulled them down at the right point. I think I had to do it a of couple times in the song.

When the song was over, I was just completely exhausted. It was the most thrilling thing I had ever experienced in my life. At that point I realized that I shouldn’t be playing guitar on the other side of the glass: ‘I want to be doing this and I want to emulate Larry, I want to have Larry’s sense of humor, and I want to be at the helm of The Enterprise, and I think I could do that and be good at that, and not be a mediocre guitar player who’s going to have to have a day job.’”

In the years that followed, Geoff set himself on course to learn as much as he could from Larry. When he wasn’t working in the studio, he was researching various recording techniques, reading S.O.S. Magazine on his lunch breaks and basically living and breathing audio.

Fate stepped in a second time. Geoff met his second major life luminary when he ran an ad for a Gibson guitar he was selling. The phone rang and it was none other than Les Paul on the other line:

“He invited me to come to the house, and I was like, ‘This can’t be real,’ you know? It was before his career had kind of relaunched itself. So there was a big gap in time in there, probably like 1963 or 1964 up to the early 70s where Les was pretty much retired and not doing anything except inventing awesome things that I got to help work on and be part of when I was at his house.

Les taught me the solution to a problem is always the simplest one. If you distill it down to, here’s the issue, here’s what’s happening, here’s how you fix it. People tend to panic when something happens but that’s often not the smartest way to approach things. He had this mid-western mechanical aptitude for problem solving.”

When we ask Geoff to share his insight on what students need to do to make sure they’re “absorbing” as much as they can he says, “I love the word ‘absorbing.’ Absorbing is what all the students should be doing. The level of absorption is directly proportionate to your aptitude and desire to do this… I’d be at work, and at lunch I would be reading Sound on Sound Magazine or something, then I’d come back to the studio at night and I would try different ideas.”

Nowadays, Geoff takes mostly a hybridized approach that combines the best of analog and digital:

“We have a two inch tape machine and we’ve figured out a way that we can track through that and have it simultaneously go into Pro Tools, and then we selectively keep and reject what we don’t want. I mean, cymbals are really bright and kind of grainy and high-end-y, and digital makes that better, because it’s the nature of the beast. I don’t really need them warmed up. I want them to kind of slash through a big, fat kick that’s been recorded at plus six on a two inch machine. Now I’ve got the best of both worlds. I have the extremities of punch and sonics, you know, from one to the other… we also mix to half inch tape a lot of times.”

Band members of Kokoros doing overdubs at Far & Away Studios

Film Connection student Ricky Long (Dayton, OH) is enjoying learning from within a professional environment: “I had the great experience of being on a well-run film shoot. After an hour and some change of watching scenes being shot, I was given the task of operating the clapper or slate. I quickly adapted. My mentor wanted me to constantly assist with camera equipment and to ask questions, but my primary personal task was to simply observe how to block actors, setup scenes to be shot, and how to navigate through the day in concerns for time.”

Film Connection student Ricky Long (Dayton, OH) is enjoying learning from within a professional environment: “I had the great experience of being on a well-run film shoot. After an hour and some change of watching scenes being shot, I was given the task of operating the clapper or slate. I quickly adapted. My mentor wanted me to constantly assist with camera equipment and to ask questions, but my primary personal task was to simply observe how to block actors, setup scenes to be shot, and how to navigate through the day in concerns for time.”

Prior to taking his final, Recording Connection student Andrew Creason (Sacramento, CA) has already landed paid work: “I have gotten my first paying client to have me mix a song. While I am excited to get my music career underway, I find it moving quite quickly. I wasn’t even expecting to have someone send me work at least untill I have finished my final mix assignment, which I am still working on. I have just sent the artist the rough mix, and was told I made her song sound much better and she is convinced that I have her music in good hands.”

Prior to taking his final, Recording Connection student Andrew Creason (Sacramento, CA) has already landed paid work: “I have gotten my first paying client to have me mix a song. While I am excited to get my music career underway, I find it moving quite quickly. I wasn’t even expecting to have someone send me work at least untill I have finished my final mix assignment, which I am still working on. I have just sent the artist the rough mix, and was told I made her song sound much better and she is convinced that I have her music in good hands.”

Film Connection apprentice/extern Charles Rocha (Washington, D.C.) shared some insight for filmmakers on the maintaining the right mindset once you get to the edit: “Don’t develop attachments to your footage…Your footage should speak for itself without you having to force your preconceived will upon it. Don’t impose YOUR structure on your material. So, perhaps consider the footage as if you found it somewhere (à la Werner Herzog, Grizzly Man). Let it tell you what it has to offer. But at the same time you have to be ruthless or you will end up with a film that is too long. On the same note, you have to have the nerve to stay away from endless tweaking and fiddling. It’s painful, but it is a profession. Craft it as a narrative; don’t raise it as a pet.”

Film Connection apprentice/extern Charles Rocha (Washington, D.C.) shared some insight for filmmakers on the maintaining the right mindset once you get to the edit: “Don’t develop attachments to your footage…Your footage should speak for itself without you having to force your preconceived will upon it. Don’t impose YOUR structure on your material. So, perhaps consider the footage as if you found it somewhere (à la Werner Herzog, Grizzly Man). Let it tell you what it has to offer. But at the same time you have to be ruthless or you will end up with a film that is too long. On the same note, you have to have the nerve to stay away from endless tweaking and fiddling. It’s painful, but it is a profession. Craft it as a narrative; don’t raise it as a pet.”

RRFC is education upgraded for the 21st century.

Get the latest career advice, insider production tips, and more!

Please fill out the following information, and RRFC Admissions will contact you to discuss our program offerings:

Stay in the Loop: Subscribe for RRFC news & updates!

© 2025 Recording Radio Film Connection & CASA Schools. All Rights Reserved.